The Fermi Paradox refers to the contradiction between the lack of strong evidence for extraterrestrial aliens and the high probability that they exist. Or, as Enrico Fermi himself put it, "Where is everybody?" There are many resolutions to this Paradox, but in this essay I explore one of my favorite: that aliens exist and are all around us, but that we humans do not recognize them for what they are. Working backwards from assuming this as true, what does it imply about us and our understanding of the Universe? I do not necessarily advocate for this idea as true, but I find it an intriguing thought experiment to explore the contours of our human perceptual and conceptual limits.

Human expectations #

When ancient peoples imagined alien creatures, they imagined a mish-mash of creatures they already knew. A centaur is a human with the body of a horse. Minotaur is a man with the head of a bull. A sphinx is a human with the body of a lion. A mermaid is a human with the body of a fish. A unicorn is a horse with a horn. Ancient artists and story-tellers, straining their imaginations to communicate to their audiences the idea of other and alien, mixed an animal or two with a human and blew everyone's minds.

Looking back, some of us might find these ideas quaint. Ancient peoples filled gaps in their knowledge with imaginary beings and outlandish cosmologies. We moderns do not know everything, but at least we have the scientific method, universal literacy and global communication. We fill the gaps in our knowledge only with facts gleaned from experimentation and peer review. But, really, humans today are not fundamentally different from ancient peoples. While we are exposed to more information and are generally more educated, we do not have more cognitive capacity, nor a greater capacity for imagination. How are our own modern stories about imaginary beings mish-mashes of that which we already know?

Star Trek and Star Wars are the most wildly popular story franchises that feature aliens, and the aliens are with few exceptions literally humanoids, each with two legs and arms, the ability to speak language, engage in business contracts or criminal enterprises, and otherwise have strong participation in human society. These fictional aliens are in essence humans. The most outrageously alien of aliens in these shows are based on some kind of animal. Occasionally Star Trek aliens are clouds or rocks or puddles of goo, but if they talk, they are humans in a costume. This is generally what our culture expects aliens to be like.

There are exceptions. Solaris, Annihilation, Arrival, to name a few recent examples. Solaris features a sentient ocean that can manifest the innermost dreams and fears of the human astronauts orbiting its planet. Annihilation features an alien presence slowly corrupting and modifying nature in an ever expanding zone around its point of impact. Arrival is about a linguist helping to decipher circular, time-independent alien glyphs. Still, I would argue that even here, these stories are less about aliens than they are about humanity. They narratively use the concept of aliens to explore human feelings around fear, loss, ecological catastrophe and the unknown, but the aliens themselves are ultimately narrative devices for us humans to understand ourselves. They are the modern equivalent of representing the idea of other and alien as a mish-mash of other more familiar elements, and not anything truly alien.

These are not digs or criticisms of our story-tellers, nor of human imagination. Stories that do not center humanity in some way are simply not interesting to us. Still, these stories point at our expectations of what aliens look like. Humans with funny ears at most comforting; ecological catastrophe against which we have no immunity at worst. To restate the thesis, I presume that aliens do not look like this because we would see them if they did. I'm arguing that, if aliens are around us, we literally cannot conceive their nature.

Human perception #

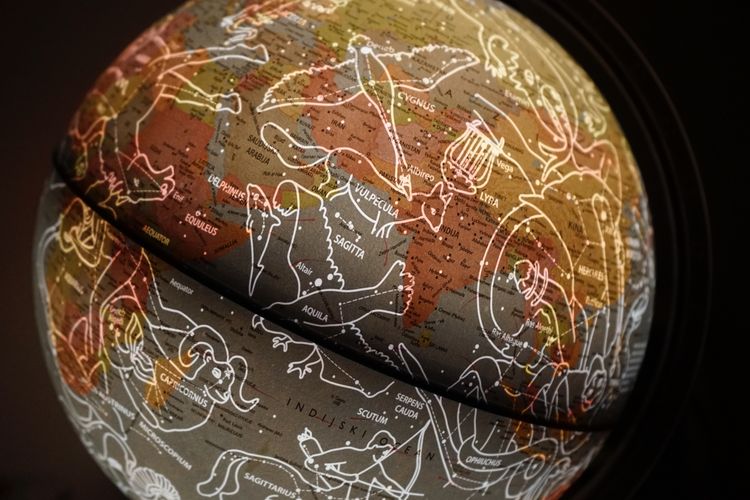

There are many perceptions that animals have that we do not: echolocation, electroreception, magnetoreception; infrared, ultraviolet, polarized light. The mantis shrimp has 12 types of photoreceptors compared to our 3, giving it access to an unimaginably rich range of colors. Still, human beings have compensated for this lack, especially within the last century. Our theories and devices help us detect phenomena of which we had been unaware for hundreds of thousands of years: cosmic rays, gravitational waves, electromagnetic waves, neutrinos. The list grows. We see and are aware of so much. The question naturally arises, "If we can see such previously unknown phenomena as neutrinos and microwaves and radiation, how can we not see something as basic and important as aliens?"

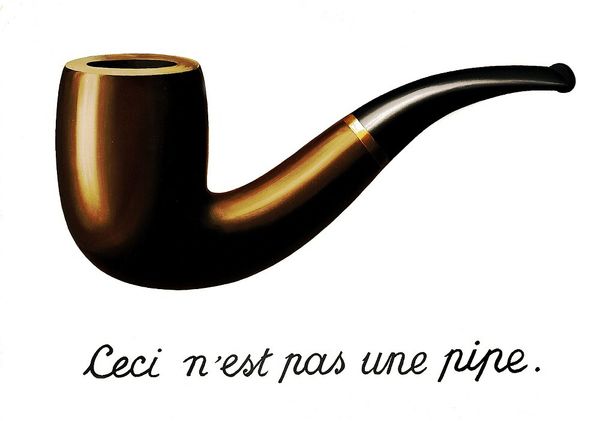

I submit that neutrinos and gravity waves and such are phenomena that map already to our perceptual and cognitive systems. Electromagnetism is a kind of light. Gravity waves are a kind of wave. We conceive of space itself in terms that are very familiar to us, and helped us survive. While our technology enhances our senses, it cannot overcome the perceptual and cognitive blind spots that have been honed and refined over eons.

My basic operating assumption here is that perception is not reality, but a kind of isomorphism or pared-down heuristic driven by the evolutionary imperative to streamline for survival. The environment in which we live is suited for our survival, and that which we perceive is only that which in some way helps us to survive. There are, however, elements of our environment that we do not perceive because the energy and distraction of doing so inhibits survival. Our environment is filled with infinitely more things that we ignore than things that we pay attention to: background noises, smells, temperature changes, air movements, time passing, the number of things. These are phenomena that we can perceive but choose not to.

I argue that our environment is filled with infinitely more things that we cannot even perceive, and furthermore I believe this should not even be controversial to say. As a straightforward but course statement of my proposition here, it is possible that we do not see aliens because it is neither necessary nor even helpful to do so.

I now bump forlornly against the limits of language in discussing the limits of perception. Just like any mystic, I must now turn to inadequate tools like metaphor and analogy and parable.

The Parable of the Aphid and The Ant #

When a European red wood ant forages for food, it might come across a colony of aphids. Aphids are small sap-sucking insects that feed on plant juices. As aphids feed, they excrete a sugary substance called honeydew that ants find delectable. The two colonies form a mutualistic relationship whereby the ants protect the aphids from the myriad dangers of the forest such as ladybugs, and the aphids - simply by feeding and living their lives - produce food for the ants. This association likely began in the Cenozoic Era, around 65 million years ago.

Is the aphid aware of the ant? Certainly aphids can perceive ants through various cues such as touch, smell and taste; but of what, specifically, are they aware? We humans have a conception of the relationship that aphids have with ants. Aphids themselves, if they conceive anything at all, almost certainly conceive of ants differently than we ourselves do. Whatever the qualia of aphid experience with respect to ants, we can be certain that concepts like mutualistic relationship and European red wood ant and millions of years are not part of it. Given that there is no fitness benefit accruing to an aphid even to perceiving their relationship to ants, we might consider the possibility that, to an aphid, ants are just background stimuli of no more importance than the wind and the grass.

It will offend the sensibilities of some of my readers when I suggest that the aphid and the ant might supply an illustration for how it is possible that one creature, such as a human, may not perceive another creature, such as an alien, and for that I am sorry. After all, we humans are the uncontested, dominant species on our planet. We detect neutrinos and microwaves and peer lightyears into the Universe. We have hunted fierce creatures nearly to extinction. We have banished and cured whole diseases that have plagued our species since the first of us. Aphids are simple, barely sensate slaves of other simple creatures. We humans can simply look up, look around, out the window, into the sky, into the ocean. See? No alien ants, stroking us for honeydew!

To all that I can only shrug sadly and say: "You're right. Ignore it. Forget I said anything about aphids."

Human Reality #

The Doctrine of Uniformity, the Cosmological Principle and the Principle of Intelligibility are all different ways of expressing the unprovable but valuable a priori assumption that the scientific laws we discover here on Earth apply throughout the Universe. Let us all just go ahead and assume that to be true. It makes these discussions easier, for one. When I argue that our understanding of what happens far away is limited, I am still assuming that there is an objective reality and that we can reason about it.

However, our most intuitive understanding of physical and chemical reactions are those that take place within an order of magnitude of around 1 atmosphere and 1 g gravity and 0.5 Gauss and within 1 day and of relatively low materials cost. This is an environment that is radically different from the overwhelming rest of the Universe. While we have theories of what happens in more exotic environments, we do generally not have an intuitive understanding of them. Only after intensive training and extensive education, some of us do gain enough expertise in physical or chemical reactions under more extreme environments such as steelmaking, deep-sea oil and gas drilling, or the interior of a nuclear power plant core, but these environments are quite tame relative to the wide extremes that exist beyond our planet.

And yet, based on nothing more than our limited experience, many of us confidently assert that the conditions under which alien life is most likely to arise are inside of a "Goldilocks Zone" of a rocky planet without too much radiation. Coincidentally, this happens to exactly match the conditions with which we are most and uniquely familiar, the Earth!

Extraterrestrial Intelligence, Number and Mathematics #

The concept of intelligence is deeply rooted in our own perception and understanding of the world around us. What we consider to be intelligence is inextricable from our uniquely human notions of survival, fitness and status. We measure intelligence based on what we ourselves consider important and imagine therefore that it is really important. Universally important. If we consider it important, then other intelligent creatures surely will as well. Which is true, but only because our conception of intelligence is stacked.

We tend to conceive of intelligence itself as a scalar quantity, a single quotient ranging from aphids to super beings. Because we assume that our approach and outlook is both intelligent and universal, we assume that any being from anywhere in the Universe within our intellectual range should be able to communicate about those intelligent things and find them enlightening and useful.

We organized the elements according to their atomic weight, and this sincerely was quite a clever thing to do. We deduced the existence of Black Holes and the speed limit of light and the distance to our sun and the ratio of a circle to its circumference and all sorts of genuinely amazing things.

Still, I suspect that intelligence is a scale that measures human interests and obsessions and not things that alien would find important and interesting. Why wouldn't an alien find the Periodic Table of the Elements interesting? It is almost inconceivable that anything intelligent would not be interested in that.

Still. Evolution and the Universe are more creative than you and I. Creative approaches to fitness in radically different environments will be multidimensional and multivalent, extremely difficult to evaluate or intuit or reason about, not because we are unintelligent, but because we are equipped neither by experience nor evolution to do so.

Alien Mathematics #

In one first contact scenario, an alien civilization broadcasts a sequence of some kind, prime numbers or the Fibonacci sequence or the digits of pi, and thereby demonstrates that they are intelligent and we are not alone. After some initial confusion and struggles, our civilizations develop a common language based on logic and mathematics, and so begins a fruitful exchange of views across the cold expanse of the galaxy.

After all, mathematics has brought us civilization and technology. We can look around and see for ourselves, in just our televisions and roads, the truth of mathematics. Surely, if aliens exist and have reached a certain level of technology, they will also be fluent in this universal language.

I am personally skeptical that mathematics is something deeper than a language that humans use to describe their perceptions of reality to other humans. I suspect that our mathematical language, which to us appears to be universal and to describe something absolutely meaningful, will really only make sense to entities that employ the same perceptual and cognitive framework for understanding, which is to say, only other human beings.

To us, our perceptions are literally universal. There is nothing to see outside of them. Also given that we are the dominant species of the planet, we have all the more reason to believe that our perceptions are universal and somehow better, more accurate, than, say, a bat's or an aphid's. We win. They lose. The End.

We humans have done marvelous things with mathematics, and mathematics clearly describes something objective, but to my mind it is speculative whether an alien species with a perceptual and cognitive system evolved entirely elsewhere under other pressures would have an understanding that intersects with our isomorphic subset of reality. A slow-moving alien that evolved in icy darkness under an ocean hundreds of kilometers deep won't be just "us, only crab" no matter how adeptly it learns to manipulate its environment. We can only imagine - or more likely, fail to imagine - what would motivate such a creature.

What would number and a mathematical system look like from creatures who thought in networks, or had no concept of "quantity" at all? I don't think an alien's perceptions and understanding would contradict our own. That is to say, 2 + 2 is 4 even on an alien planet. But if it is true that our perceptions are a kind of isomorphic heuristic that maps onto reality and elides that which is useless or distracting, then an alien's understanding - that which it found important in environments entirely different from our own - might include elements of reality that we literally can neither perceive nor even understand.

Could the concept of "number" itself could be an artifact of human perception? It enabled our ancestors to survive our niche, planetary environment, but perhaps it's not an inherent feature of objective reality. Perhaps numbers exist in the same way that red exists. Aliens, evolved to survive in another environment entirely with a different set of initial conditions, almost certainly would not have the same understanding of "number" that we do.

Alien technology and convergent evolution #

We have a general expectation that intelligent aliens will have technology more or less similar to ours, but let's examine what would be necessary for that to be true.

Under Earth-like conditions it's definitely possible to imagine biomechanical convergent evolution: wings and fins and legs and claws and teeth and alimentary canals and eyes and gills and so forth. As with Earth creatures, these imaginary Earth-like aliens exploit mechanical principles with which we ourselves are familiar. Their bodies are constructed of variations of basic levers and wedges and screws and wheels and wings.

So far, sure, I don't have any major objection. I do think it's at least possible that we humans are not familiar with all of the biomechanical strategies for survival that are possible even in Earth-like conditions, not even to mention biochemical strategies, but let's assume that all creatures on our Earth-like alien planet are recognizable to us as creatures.

Technology clearly is an extension of ourselves and our needs. Our need to move and carry things leads to the cart, chariot and car. If our bodies were sessile like plants, we would not have invented a car. Our need to calculate and communicate leads to the laptop. And so on. Marshall McLuhan held that technology is literally an extension of our bodies: wheels are an extension of our feet and the telephone is an extension of our mouths and ears.

Perhaps some of the creatures on our extraterrestrial Earth-like planet use materials in their environment to construct what we would label technology. These creatures, having evolved in similar environments and under similar pressures as we have, produce machines that we ourselves would recognize and find useful: spears or stairs or boats, for example. Perhaps one of these pieces of technology serves their need to emit calls in their Earth-like atmosphere, but instead of sound waves, it emits electromagnetic signals into space. Perhaps we then intercept those signals. Furthermore, because of convergent evolution, their psychology leads them to seek companionship and desire to communicate with others. They use distinct ideas recognizable to us unlike, say, whale song or pheromones.

It is by this quite unique scenario, this implausible sequence of events, that of creatures rising into the sky from an exceedingly rare environment even in our own solar system, that most of us expect to meet aliens. However, not only is the sheer physical, mechanical sequence of events unlikely, but whatever emerges is even more unlikely to have anything meaningful to say to us.

So Aliens, then? #

Extrapolating from our single data point, the Earth, about what life is like on other planets is a Rorschach test. Any assertion says more about the person asserting than it does about the Universe itself. So I'll just put my own cards on the table here and talk about what I personally speculate is most likely if this particular resolution to the Fermi Paradox happened to be true.

I'll give a specific example from our own planet. Imagine that trees are sentient and have their own literature and mathematics. However, they express their literature and mathematics to each other only through slow, decades-long chemical processes akin to releasing pheromones, only underground, via their interconnected root system. How would we ever know this, much less understand what it is they were communicating to each other? We never would. We would always assume as we do now that trees are alive but insensate. Bear in mind that "trees" are far closer to us than aliens are likely to be. There are a few Earth creatures enough like us that we might imagine they have things to say to us, but they never, ever do: dolphins, whales, octopuses, apes, for example.

I believe that we would consider aliens to be insensate, natural processes if we considered them at all. Lumps on the surface of a planet because of wind and sand. Mere Gaussian noise across the broadcast spectrum. Spectacular electrochemical eructations across slowly billowing nebulae. We would neither communicate with nor even perceive them because there is no real need to do so, and no method to do so. Communication, technology, language, science and mathematics - the tools through which we expect to interact with aliens - are uniquely human tools to communicate with human beings.

The Fermi Paradox resolution in a nutshell: aliens are all around us but are just too unimportant.

Reading List #

- Life beyond Earth : the intelligent Earthling's guide to life in the universe - Feinberg, Gerald (1980)

- Understanding media : the extensions of man - McLuhan (1994)

- "Alien Intelligence and the Concept of Technology" : Stephen Wolfram Writing - Wolfram (2022)

- "Why Extraterrestrial Life May Not Seem Entirely Alien" : Quanta Magazine - Wolagiewicz (2021)

- The Great Filter - Are We Almost Past It? - Hanson (1998)

- An objective Bayesian analysis of life’s early start and our late arrival - Kipping (2020)

- Grabby Aliens